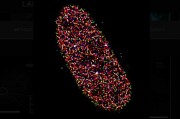

Researchers at Aalto University have induced in room temperature a Bose-Einstein condensate of light coupled with metal electrons in motion in gold nanorods arranged into a periodic array.

Bose-Einstein condensation (BEC) describes the phenomenon predicted by Albert Einstein and Satyendra Nath Bose that quantum mechanics can force a large number of particles to behave in concert as if they were only a single particle.

In 1995, scientists actually created the first such condensate of a gas of alkali atoms. Since then, scientists have been working to push Bose-Einstein condensation to faster timescales, higher temperatures and smaller sizes, with the goal to create, for example, extremely small light sources and enable superfast information processing.

The new Bose-Einstein condensate

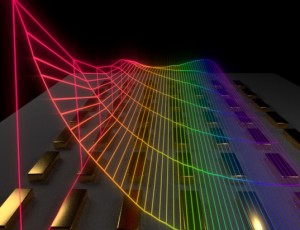

Now the team in Finland induced a new Bose-Einstein condensate at room temperature. “The particles that condense are hybrids of light and electrons in motion, so-called surface plasmon polaritons,” says Academy Professor Päivi Törmä in the Department of Applied Physics at Aalto. “They are mostly light, but contain also a small part of electron plasma oscillations in gold nanoparticles arranged into a periodic array.”

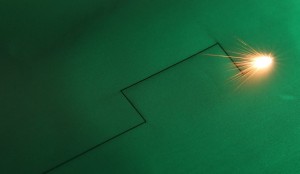

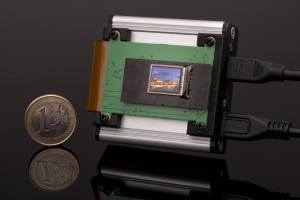

What is unique about this condensate is that this, according to the professor, is the first Bose-Einstein condensate in a plasmonic system, that is, of light coupled with electron plasma oscillations. Moreover, unlike most other condensates, it forms at room temperature. “It is also among the fastest condensates, namely, the condensation happens in one picosecond,” Törmä says. “The fabrication process for this condensate is particularly easy, since it can be done with standard nanofabrication methods, such as electron beam lithography. The geometry of the array can be varied easily to modify the properties of the condensate.”

The difference between Bose-Einstein condensation light and laser light

Törmä elaborates that both Bose-Einstein condensation light and laser light provide a bright beam, but the coherence properties can differ. For instance, the Bose-Einstein condensation light can have different fluctuations and correlations than laser light.

New applications

In the future, this new Bose-Einstein condensation could perhaps enable entirely new kinds of applications not yet feasible. However, the professor says: “At the moment it is hard to say whether this condensate will offer applications that, for instance, polariton or photon condensates cannot.” She points out that more basic research will need to be done to understand what are the specific features of this condensate that could allow applications that other condensates cannot. “But certainly our condensate is very easy to make, ultrafast, on-chip and has a small footprint, which are all advantages concerning applications.”

The discovery’s impact on the future of light-based technologies

“Our discovery, together with other luminous condensates, suggests that we should not be limited to think only of lasing and spontaneous emission as the processes that can produce coherent and incoherent light, respectively,” Törmä points out. "There can be other processes, such as Bose-Einstein condensation, that produce light with properties we have not seen before. The way we utilize light may change.”

The next step

In the new system Törmä and her colleagues have created it is very easy to realize either conventional lasing or BEC: To vary between these two, they simply need to change the distance between the particles in the periodic array. “Therefore, we can study the crossover from lasing to BEC to better understand how these phenomena are related and differ,” she says. “Another interesting future direction is to increase the amount of dye molecules in the system so that we reach strong coupling between them and the plasmonic modes, and see how this affects the condensation phenomenon.”

Written by Sandra Henderson, Research Editor, Novus Light Technologies Today

Back to Features

Back to Features