Having worked for several years in optics as both a top academic and a Fellow at Zeiss, Michael argues for greater career switching between academia and industry and provides some pertinent and illuminating insights into different perspectives on technology.

Career background

After a degree and PhD in physics, Michael began his distinguished academic career as a postdoc at the Technical University of Berlin, leading a workgroup on waveoptics. In 1995, he moved to the University of Stuttgart where he founded and led a group on quantitative microscopy. In 2002, Michael was invited to join Zeiss as a Principal Scientist to work on the design and simulation of lithography optical systems.

The idea of working for a company had never occurred to Michael, in fact, he confesses to having had a number of anti-industry prejudices. But this move was both life and career changing and a decision he has never regretted - "I learned how cool and innovative it was to work in industry and I was absolutely thrilled with the work the breadth of the topics that were absolutely cutting-edge".

Starting out as director of the metrology department of in Zeiss's Corporate Research and Technology, Michael rose to Senior Principal and then in 2015 to a Fellow in Zeiss's expert career path.

However, unlike many who make the transition from academia to industry, Michael managed to continue his academic career by becoming an Honorary Professor in Optics at the University of Konstanz. With this position, he was able to combine his work at ZEISS with teaching optics, supervising research projects and publishing research papers.

Michael believes his career to date underlines the following points:

1. Working in academia and industry is compatible. Contrary to a widespread belief, it is possible to work simultaneously in academia and industry and working in one sector does not and should not entirely preclude working in the other.

2. There is a need for greater permeability between academia and industry. There needs to be a change in culture that encourages movement between the sectors, for example enabling professors and people from industry to do exchange sabbaticals. Such a program has started at Zeiss with the creation of a two-year Zeiss postdoc to enable students to publish and obtain a career boost by working inside a company for 2 years.

3. In terms of publishing, there is not necessarily a conflict between academia and industry. Of course, the goals are different: academia aims to contribute to scientific knowledge while the main goal of company R&D is to create business and it's true that in-company publications are sometimes used as a marketing tool. However, as Michael argues, this kind of contradiction can be resolved by considering the technology readiness level. If you are in a very early stage of the technology and readiness level, then it may be more appropriate to publish a paper on the scientific aspects. Alternatively, if you have an idea how to use the technology to create business you can either patent it or put into a company to move forward.

4. Patents. In industry you write much more patents than papers. Michael, e.g., authored and co-authored about 70 patent families, each usually comprising several documents. Patents are indeed a very important form of technical publication. ,

5. Different perspectives on technology. One of the risks for academics is that they can become extremely focused on one technology. "In industry you can't afford to be the world expert on just one technology because when you 'marry' a technology and a better one comes along, you are out of the market." Michael stresses the fact that in industry, there's always the requirement to look at customer issues and how they can be solved. This requires being technology agnostic and able to embrace the enormous breadth of technologies available together with the ability to judge their relative merits.

One way to conceptualise this is with a T model: "the horizontal bar of the T represents a good understanding and overview of the many technologies available while the vertical line represents the one or two technologies you understand in real depth." In most cases, the higher you rise in a company, the more important the overview becomes.

Evaluating new technologies

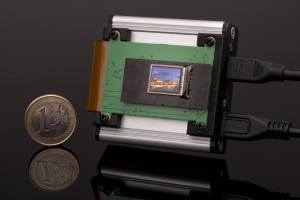

An important part of Michael's work at Zeiss is to judge the future potential of new technologies - to weed out the hype and determine what really has a sound basis and is in the long run interests of the company.

For Michael, the major difference between academia and industry is that " as an academic you can be interested in a technology just for itself, but in industry you can only consider the state-of-the-art: Far more important than that a technology is new, is that it is able to create a new impact for customers."

However, evaluating the potential of new technology is not always easy as what may initially be regarded as hype can later come to dominate the market. A case in point is digital optics, which for many was originally considered as hype but is now shaping the overall field. One reason is that it provides 'additional degrees of freedom' to separate contrast generation from taking the image.

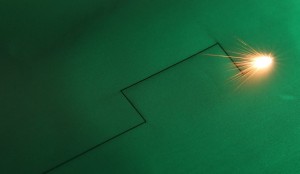

The ability of new technology to provide additional degrees of freedom is an important factor in determining future potential because it can be used and leveraged to provide solutions and create additional customer value. This applies for example, to ghost imaging and the use of quantum technology. In Michael's view, this technology has a clear future because it gives additional degrees of freedom in resolving the problem of how to separate the interaction a light with an object from the interaction of light with the sensor. 5D imaging, which involves hyperspectral imaging overtime, is another candidate as it provides additional degrees of freedom in obtaining more information when imaging in parallel.

But it’s not only new technologies. It’s also new experts. So, a further important part of Michael’s work is to develop TOP experts in the expert career path.

What would you have done differently?

"I would have moved to Industry earlier because when I discovered how interesting industry is it gave my life a new dimension." Michael feels that he probably stayed too long as a postdoc but recognises that at that time there was still a separation between industry and academia and it was far more difficult to create startups.

Advice to PhD students

"Get into interaction with industry early: make a conscious decision to do this and don't be influenced by prejudices." In Michael's experience, just working in an academic institute doesn't enable a student to really know about industry culture and how people interact: it was only when he did in the course of a joint project part of his job at Zeiss that he really learned what it was like to work in industry.

"As a postdoc you really need to judge realistically your chances of becoming a professor. It's always advisable to have a plan B so you have at least two career options." But even if a student wants to stay as a postdoc and successfully carve out an academic career, Michael's advice is that they should still collaborate with industry as "this will give you an insight into cutting-edge challenges and demands, obtain revenue for your group and keep the door open for a potential career move into industry".

Finally, it's also important to bear in mind that a move to industry requires adapting to a sharing culture in respect of technology and also the development of leadership skills in order to supervise and inspire people, trigger ideas and serve as role model.

Written by Jose Pozo, Director of Technology and Innovation at EPIC (European Photonics Industry Consortium).

Back to Features

Back to Features