In this interview, Antonio Castelo, PhD, EPIC’s Technology Manager for Bio-Medical and Lasers, talks to Jan Hostaša, co-founder and head of R&D at Zenit Smart Polycrystals, an Italian producer of transparent polycrystals for enhancing the performance of laser systems and semiconductors.

What’s the background to you co-founding Zenit Smart Polycrystals as head of R&D?

In 2010, I completed an MSc in Chemistry and Materials Engineering at the University of Chemistry and Technology in Prague (UCT), which included a four-month internship at the Institute of Science and Technology for Ceramics at the Italian National Research Council (CNR).

I did my PhD in Chemistry and Technology of Materials at UCT Prague, focusing on transparent YAG ceramics for laser applications. Part of the research was done at the CNR in Italy, where I continued as a Researcher in the Transparent Ceramic Group.

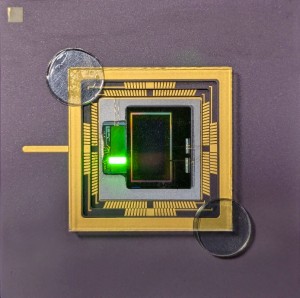

In 2020, our group patented a process that exploited 3D printing to shape transparent polycrystalline components with complex geometries and a chemical composition that could vary in three dimensions, mainly for applications in solid state lasers.

Then came COVID, which gave us quite a lot of time away from the lab that we used to explore the commercial potential of the technology we’d developed. By the end of lockdown, we’d drawn up a business plan, which we presented in 2020 as part of two innovation competitions for Italian startups, first regional (StartCup) and then national (PNI).

We got to the finals of both of the competitions, and apart from the visibility we received a positive feedback and advice, which convinced us that the commercialisation of polycrystals was feasible, and to this end, in September 2021, I co-founded Zenit Smart Polycrystals as a spinoff from the CNR, with me as head of R&D.

What convinced you Polycrystals had commercial potential?

Additionally, the application of 3D printing allows variations in the type and distribution of the dopant ions in the three dimensions of the component. This means that the shape could be controlled from the beginning, and also the possibility of making micro composite photonic structures[JH1] .

How has the company developed?

Fortunately, the CNR is quite spinoff friendly as they have a system that allows the creators of spinoffs to stay working as a researcher at the CNR while simultaneously dedicating part of their time to the company.

This opportunity gave us time to go through the proof of concept phase and validate the technology. In our case, although we had a patent, it took time to bring it from the lab to industry and make sure that the process was bulletproof.

Since then, product development has been mostly based on feedback and discussions with our clients making sure the product exactly meets their needs and is replicable.

How did you find the transition from academic research to industry?

It's like going from one world to another. Typically, in academic research, if you prepare, say, 10 demonstrators and one of them passes all the required tests and the other nine don’t, it’s seen as a success. But in industry, if a company produces 10 parts and only one of them works, it’s considered a failure.

For this reason, we had to develop the technology in a more systematic way - to be certain about reproducibility. In academia, you don't have the time and space to do this because it’s the research that’s important rather than the practicalities of commercial applications.

What were your main personal challenges when you started with the company?

Having only ever worked as a researcher, I was totally unprepared for the business, financial and managerial side of things.

The biggest help for me in these areas was our involvement in the competitions for Italian startups. It wasn’t just a case of presenting our ideas - it included an incubation part where we talked to experts who reviewed our business plan and asked questions we hadn’t thought of or had tried to avoid. This really helped my understanding of what we needed to focus on in terms of building the company.

How receptive are potential customers to your technology?

I have to say that the market is not as flexible as we expected, but there are also a lot of differences between the potential customers. Some of the longer established companies have experience with transparent ceramics, and in cases where the experience wasn’t positive, it can be problematic. Others are happy to continue using single crystals for their lasers because they are reluctant to change suppliers.

But others are really open and interested in our solutions. In these cases, we first make a direct comparison what with what they have and then follow up by showing them the added value our technology can offer.

How do you see the future?

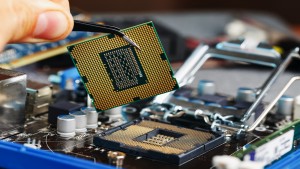

As regards competition, for the moment, our technology has advantages that distinguish us from others especially single crystal producers. Looking forward, we have three main goals. Firstly, to establish clear protocols for quality control that can be followed by the whole team. Secondly, although laser polycrystals will remain our core business, we will need to continue with R&D to be able to address emerging markets.

Thirdly, and most importantly, we will need to get better at educating the market and explaining the advantages of our technology to prospective customers. It's not just about replacing single crystals with polycrystals - it’s about giving added value. For example, in lasers and photonics, with polycrystals you can introduce wave guides or extra cladding in some part of the component, which with single crystal bonding would be really difficult and expensive.

If you started again, what would you do differently?

I’d try to use my time more productively. When we started, we all did a little bit of everything. In my case, I was involved in looking for funding, looking for customers and partners, adjusting the technology as well as a lot of administrative stuff. What I came to realise is that for me, spending time talking to clients was much more useful for the company than spending time on, say, funding applications, a complex and time consuming task. In retrospect it would have been better to pay someone with specialist knowledge in this area which would have enabled me to use my time more profitably.

What’s your advice for the next generation of entrepreneurs?

When you start a company, apart from the technology, you know very little. So don’t be afraid to ask for help and support. You will need to interact with investors and explain the commercial potential of your technology and why it’s unique. For this you will require data and numbers, not just feelings. If you are in a university, you can get a lot of information and advice from the people who deal with tech transfer, but you need to ask, talk to people.

It's also crucial to go to trade fairs where you can talk to producers with experience of the market. In this respect, being a member of EPIC has been very helpful for us because we’ve been introduced to the right people covering the whole value chain, which has saved us a lot of time and effort.

Back to Features

Back to Features