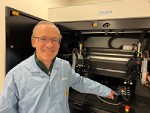

In this article, Jérémy Picot-Clémente, EPIC’s Photonics Technologies Program Manager, talks to Thierry Georges, President and Technical Director at Oxxius, a French designer and manufacturer of advanced laser systems.

What’s the background to you founding Oxxius?

In 1989, after completing a degree in Telecommunications at Telecom Paris, I joined France Telecom CNET, now Orange S.A, as a research engineer. In 1994, I completed a PhD in Telecommunications at Telecom Paris and led a team on the development of optical amplifiers and very high bit rate transmission. Our team was the first in the world to achieve one terabit per second data transmission over 1,000 kilometres. The technique we developed was initially based on a technique for submarine transmission but modified with forward error correction to overcome bandwidth limitations.

By the end of the 1990s we were transferring a lot of products to SMEs in France such as tuneable lasers in the 1.5 micron band and doped fibers for amplification. This was the time of the telecom bubble, and in 1999 I decided to set up my own company Algety Telecom in Lannion, France, as CEO. My aim was to develop and manufacture optical transmission equipment, particularly for Dense Wavelength Division Multiplexing systems to meet the growing demand for bandwidth driven by the rise of the internet and data services.

Initially, we did well, developing a network of customers in the US and growing our workforce from 20 to 250 in less than two years. But then came the telecoms crash, and in 2000, Algety Telecom was acquired by Corvis, a U.S.-based optical networking company, who were attracted by our contacts with US operators.

Things then went from bad to worse. Corvis became an operator and all work on developing telecom systems was stopped. As a result, in 2002, I set up Oxxius with a friend with the aim of designing and manufacturing advanced laser modules, particularly diode-pumped solid-state (DPSS) lasers and laser diode modules for applications in bio-photonics, metrology, spectroscopy, and other analytical and instrumentation fields.

How has the company developed?

In the early 2000s, lasers used for scientific research and spectroscopy were mainly ion and gas lasers, which were bulky, consumed a lot of power, produced a lot of heat, and were difficult to use in instruments. We therefore saw a gap in the market for DPSS laser systems that were compact, more efficient with lower power consumption, particularly in the 488 nm (blue) and 532 nm (green) wavelengths.

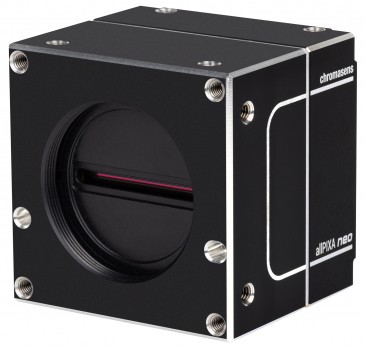

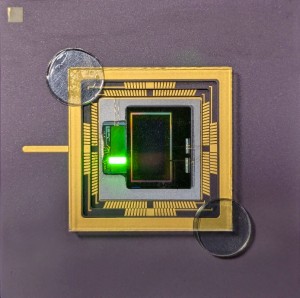

Since then, we’ve developed a range of continuous and modulated monolithic DPSS lasers that incorporate a proprietary monolithic resonator that integrates all critical optical components—such as the gain medium, frequency conversion crystals, and resonator mirrors—into a single, ultra-low-loss optical block, eliminating the need for alignment. In addition to being alignment free, our laser systems have the advantages of being compact, more reliable, more stable, more robust, and suitable for a wide range of applications. Our main markets are interferometry, Raman spectroscopy fluorescence microscopy, and industrial applications.

Since 2002, our workforce has grown to 68 and we ship around 1,500 laser systems a year.

What have been your main personal challenges?

With a small team of 10-15, managing people is a pleasure. But with bigger teams, the expectations of people are very different and are more difficult to manage. Sometimes when an employee is not happy the best solution is to move elsewhere and find a better situation. But for me, when I see unhappy people it's difficult. For this reason, I decided to hire a new CEO last year and continue in the company as President and Technical Director, so now I'm in charge of a team of 15 people which I like much better.

With a small team of 10-15, managing people is a pleasure. But with bigger teams, the expectations of people are very different and are more difficult to manage. Sometimes when an employee is not happy the best solution is to move elsewhere and find a better situation. But for me, when I see unhappy people it's difficult. For this reason, I decided to hire a new CEO last year and continue in the company as President and Technical Director, so now I'm in charge of a team of 15 people which I like much better.

A second challenge was between 2010-2013, when our VC quit, and because we had no external money, I had to buy their shares with my own money. This was followed by a dispute regarding the need to develop an assembly process that was suitable for shipping. I came under pressure from the team to abandon the monolithic approach and do what other companied did. But I persisted because I knew that if we adopted a different approach, it would take 10 years to stabilize the product. Fortunately, in 2015 I found a solution. As the saying goes “everything that doesn't kill you makes you stronger”.

What is your added value compared to your competitors on this market?

What sets our lasers apart from our competitors in the DPSS laser market is a combination of stability, spectral quality, compactness, efficiency, and above all the lifetime of our products. The typical lifetime of our monolithic DPSS Lasers is up to 100,000 hours due to the robust monolithic design, no alignment-sensitive components that drift over time, minimal thermal and mechanical stress, the use of long-life diode pumps and high-quality crystal bonding. Also important is capacity in that our laser combiners can incorporate 6 combined wavelengths, ranging from 375 nm to 1064 nm, with output powers up to 500 mW per wavelength in the same box.

What are your main business challenges?

Our main customers are instrument makers, e.g., microscopes and Raman spectrometers and we have a worldwide customer base. These types of companies make a new generation of products every 5-8 years, and when they do, they have to decide whether to keep their existing laser supplier or look for a new one. Once they decide, they don’t normally introduce a new laser so if we are accepted by a customer, we know that within the next four or five years we will have to ramp up. But the window of opportunity to get new customers is only one once every five or eight years. Of course, companies make several products and so we may have more opportunities, but it takes between 5-8 years to really to address the whole market.

How do you see the future?

Very bright. Over the next 4-5-years we expect to at least to triple our revenue and increase production of laser systems from 1,500 to 5,000. These predictions are based on the fact that two years ago we launched a fourth generation of product that allows the use of nonlinear crystals that are good for short wavelengths and high power. Two years ago, it was difficult to make half a Watt in green but now in the lab we can make 2 Watts in green, and I've ordered some diodes with twice the power just to demonstrate 3 or 4 Watts. Having little or no limitations in either wavelength or power means we will be able to develop a lot of new products in the UV and blue wavelengths.

What’s your main piece of advice to the next generation of entrepreneurs?

If you make a product or you have an idea, don't keep it in your lab, think about how you can turn it into a company. You may not be successful the first time, but you will learn a lot of things. In France 20 years ago, failure was seen as very negative. But now, fortunately, you are allowed to fail. In the worst case scenario, you can go back to university or become an advisor to a company.

In this context, it is pleasing to note that the French photonics community is doing a lot more than previously to promote photonics innovation. For example, the Jean Jerphagnon Prize, which I am involved with as a member of the jury, is awarded annually to honour outstanding contributions in optics and photonics. Similar awards are presented by Photonics France, the French Optical Society and the French Ministry of Higher Education.

Back to Features

Back to Features