The mesmerizing high-resolution images NASA’s New Horizons spacecraft shot back during its recent Pluto flyby became an overnight internet sensation. But photos, while worth a thousand words, really only tell half the story. And the famously demoted dwarf planet, sitting at the ragged frozen edge of our solar system, sports a surface comprised of as much mystery as methane ice.

That is, until now.

A long horizon

Thirteen years ago, my colleague Ken Rosenberg and I undertook an ambitious NASA project to lead a team to design and build a filter assembly that could fly to Pluto on a spacecraft and map the composition of the dwarf planet and its binary twin moon Charon.

The filter would fly on the New Horizons spacecraft, eventually launched in 2006, and arrive at Pluto nine years later, on 14 July, 2015. The instrument incorporating the filter assembly was called the Linear Etalon Imaging Spectral Array – “LEISA,” for short –, part of the Ralph instrument package and one of seven packages aboard New Horizons. It was dedicated to one of what NASA calls the Group 1, or primary, mission objectives to map Pluto and analyze its composition.

So how does it work?

Pluto’s composition would be analyzed spectroscopically, by imaging the surface in a range of infrared wavelengths and reading the local spectral signature of each material. Conventional grating spectrometers were too large and heavy for the mission, so the NASA team chose an architecture based on linear variable filters (LVFs). LVFs are narrow bandpass filters whose bandpass varies with physical position along a line on the filter.

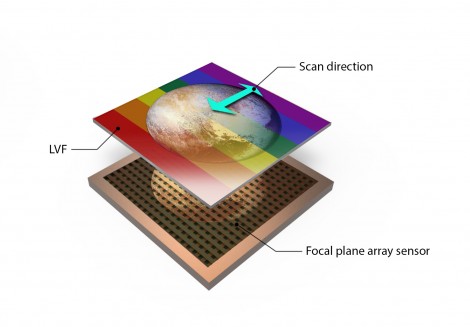

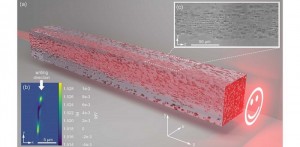

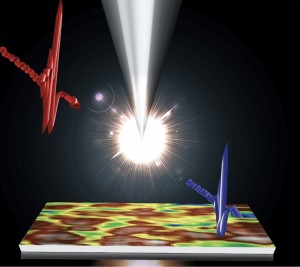

When an LVF is placed in close proximity to a detector array, the resulting sensor becomes a spectrometer. If the detector array is two-dimensional and placed at the focal plane of a scanning imaging system, as it was in the LEISA instrument, it becomes an imaging spectrometer [see figure below]. The resulting instrument is about the size and weight of a golf ball, perfectly suited to a lightweight, high-speed spacecraft.

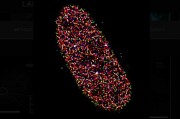

Schematic diagram of the spectral imager aboard New Horizons. The rainbow colors on the LVF represent lines of constant bandpass wavelength in the short wave infrared. The image of Pluto is scanned over the LVF and focal place array by the spacecraft motion, enabling the sensor to accumulate a full spectrum for each point on Pluto's surface.

The filter assembly we designed actually comprised two LVFs. The first of the two was designed to cover a wide range of wavelengths in the short wave infrared (SWIR) from 1.25 to 2.5 microns. That spectral range contains the chemical signatures of water, methane, and nitrogen ices, three constituents likely to be found on Pluto’s surface. The second LVF covered a much narrower range, 2.1 to 2.25 microns, at higher spectral resolution, to look specifically at nitrogen bands used to measure the dwarf planet’s surface temperature near 35 K. The LVFs were actually not linear, but varied logarithmically with position, to maintain a constant spectral resolving power (λ/Δλ) across the full range [K. P. Rosenberg, K. D. Hendrix, D. E. Jennings, D. C. Reuter, M. D. Jhabvala, A. T. La, “Logarithmically variable infrared etalon filters,” Proc. SPIE 2262, 223 – 232 (1994).].

The two LVFs were bonded, edge to edge, in the final assembly to enable the single detector array to map both composition and temperature. The technical requirements for spectral bandwidth and out-of-band blocking were beyond any our team had done before, nor had an LVF ever flown in space.

Filter development and testing took two years. Each filter was computationally designed, carefully fabricated, and tested numerous times to ensure it consistently met all the stringent optical, mechanical, chemical, and environmental requirements. Needless to say, there is no service call for a failed filter when a spacecraft is hurtling through the solar system at 30,000 miles per hour on its way to a rendezvous with a dwarf three billion miles away.

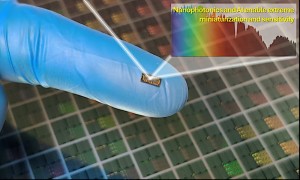

The Ralph Instrument Package. Image courtesy of SWRI

In 2004, the fully tested and qualified assemblies were delivered to other partners in the project who mated the filters to the detector arrays and integrated them into LEISA and, in turn, into the Ralph instrument package. The detectors were 256x256 pixel mercury-cadmium-telluride (HgCdTe) arrays placed at the focus of the 75 mm, f/8.7 Ralph telescope. [For more on the Ralph telescope, see D.C. Reuter, et al. “Ralph: A Visible/Infrared Imager for the New Horizons Pluto/Kuiper Belt Mission,” Space Sci Rev 140: 129–154 (2008)].

Deep inside, our LVF assembly was delicately but securely perched 100 microns above the detector surface to minimize spectral broadening as the beam propagated from filter to detector. After we shipped the filters, we went back to work and later developed miniature LVF-based spectrometers that today ensure the quality of food, feed, and pharmaceuticals.

Launch time

We didn’t give our LVF assemblies another thought until 19 January, 2006, when New Horizons took to the sky from Cape Canaveral. Thanks in part to the compact spectral imager enabled by our LVFs, the spacecraft was light and speedy to make the three-billion-mile trip in “only” nine years. On the way, it flashed by Jupiter to get a gravitational boost and test out its instruments, which proved their mettle. And on 14 July of this year, exactly as planned, New Horizons went screaming by Pluto at 30,000 miles per hour, furiously snapping pictures and gathering data that will take another 16 months to fully send back to earth. The LVFs, the LEISA spectrometer, and the Ralph instrument package performed flawlessly. Among the first information sent back to earth were the answers to those critical Group 1 questions.

Window on a remote world

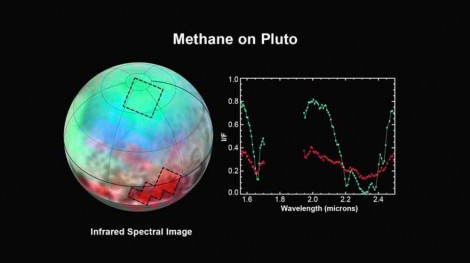

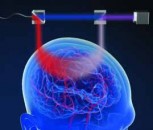

Map of Pluto's composition assembled from spectroscopic images taken by the LEISA instrument (Image courtesy of NASA).

And what is it made of? Equally surprising, it is more than one substance. Methane ice, as expected, covers most of the surface, but large areas of the dwarf planet, including the north polar cap, are coated with nitrogen ice – without any obvious explanation (see Figure). This is a puzzle scientists will be working on for years to come.Map of Pluto's composition assembled from spectroscopic images taken by the LEISA instrument (Courtesy NASA).So, what does the surface of Pluto look like? The surface, to the surprise of planetary scientists everywhere, is remarkably featured. With 11,000-foot-high mountains and evidence of relatively recent volcanic activity, that dwarf at the edge of the solar system is anything but dull or faceless.

While they do, New Horizons will continue its voyage of discovery into the Kuiper Belt, an even more distant, asteroid-belt-like region of remnants from the Solar System's formation where, no doubt, LEISA will send back more surprises for planetary scientists to puzzle over.

Written by Karen Hendrix, Principal Filter Designer, Viavi Solutions Optical Security and Performance Products

Back to Features

Back to Features