The illegal global trade of endangered and protected wildlife, linked to organized crime and terrorism, is worth up to $20 billion annually. Rhino poaching in particular is big (illegal) business; rhino horn is worth more than gold on the black market per kilogram.

Poaching: Threat to rhino population

The Kifaru Rising Project is focusing on the black rhino, one of the world’s most endangered species. There are currently 760 black rhino in Kenya, which is the most of any country in east Africa; however, the population is threatened by poaching, which is the leading cause of declining rhino populations. According to Colby Loucks, WWF’s Vice President of Wildlife Conservation, there has been a massive increase in poaching of rhinos over the past ten years. For example, in 2007, 62 rhinos were poached, while in 2015 the number rose to 1349. The impetus is the demand in Asia, where the horn is predominantly used in traditional Chinese medicine, but is increasingly being used as a symbol of wealth and prosperity.

Loucks reported that a single pound of rhino horn is worth about $27,000. For comparison, the price of a pound of gold is currently $26,512. And a single horn weighs on average 5 pounds – therefore on average each horn is worth $135,000 in Asia – though the poachers get a fraction of this amount.

Poachers in the line of sight

Since 2019 the World Wildlife Fund (WWF) has been working with the Kenya Wildlife Service and FLIR on the Kifaru Rising Project to reduce poaching throughout 11 parks and game reserves in Kenya. World Wildlife Fund’s goal is to get to zero poaching of rhinos and other highly endangered or poached species such as elephants. He noted that there are a few factors at play that hinder their efforts, such as climate change. But, he added, “You can’t be successful if you don’t try.”

The project will leverage the experience gained through the projects already underway and will go a step further by deploying thermal imaging technology more broadly. FLIR has pledged more than $3 million in equipment, engineering assistance and training for this project, with the goal of eliminating rhino poaching in Kenya by 2021.

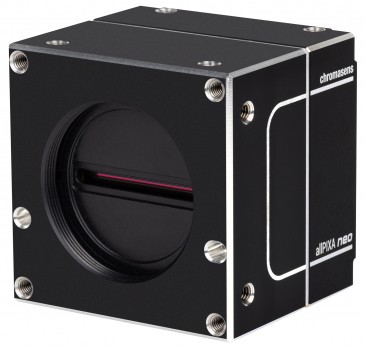

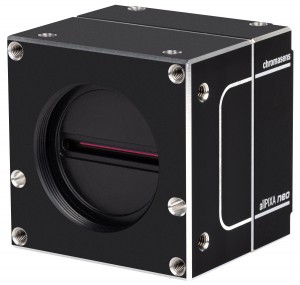

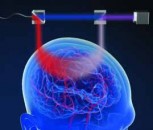

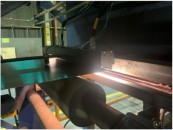

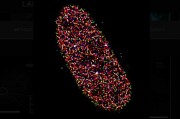

The poachers bring serious weaponry into the preserves, which spells significant danger for the wildlife rangers as well as the rhinos. FLIR responded with a broad range of surveillance equipment, which includes professional grade thermal handheld cameras, fix-mounted perimeter security cameras, drone cameras, and automotive.

Shawn Jepson, FLIR Security Solutions Architect and lead FLIR engineer on the Kifaru Project, provided insight into the types of cameras in use. Fixed cameras are connected via a network, and the data goes back to command station in the park. Rangers all have radios, and if there is activity in a certain area, a person in the command center will monitor the cameras in that area, providing situational awareness to the rangers. In some cases, the person monitoring the images has a GPS and can provide coordinates so the rangers can pinpoint the location.

The thermal handheld cameras are similar to what frontline responders use. These cameras are not connected to the network, but because they are not fixed, they enable the ranger to take the camera under bush and in areas that a fixed camera might not be able to spot. The rangers may be on patrol for 2, 4 or 6 months at a time, and having a handheld camera with them lets them assess potential situations on the spot.

Vehicle-mounted cameras have been in use for some time, even before FLIR got involved with the project. The benefit of having these cameras is the mobility. “They can drive to a high spot and scan the region, or sometimes they get a heads up from locals as to activity in an area,” Jepson explained.

FLIR also provides drones with cameras mounted on them. These have proven to be of great benefit, as they can survey areas that nothing else can. For example, should rangers hear gunshots in the bush during the dark of night, rather than charging into what would likely be a dangerous situation, the rangers can deploy a drone with cameras that could spot the poachers in the grass and light them up so they could be found by the rangers. “The drones eliminate a lot of uncertainty and reduce danger to the rangers,” Jepson said.

Challenges

The partnership with FLIR is one of the WWF’s most substantive technology projects to help stop poaching. Loucks said that the challenges of taking technology into some of the most isolated and wild places on Earth are many. “But our vision with FLIR is to show that if we can be successful in these places, then the idea and technology can be successful elsewhere.” While surveilling vast wilderness poses danger to the rangers, other threats are posed by wildlife damaging equipment. “Some of the more unique challenges have been baboons climbing our masts and then tearing off our solar panels which provide power to the FLIR cameras, build-up of dust and dirt on the camera lens, elephants knocking over masts that hold cameras,” Loucks explained.

Another recent challenge is COVID-19 because Kenya is currently under lock-down and the teams from WWF and FLIR have been unable to travel to Kenya to help finalize the installation of additional cameras, however, they do continue to work with them through video conferencing. The lack of tourists also causes some worry because tourists serve as “eyes in the park,” helping to deter poachers, Loucks said. He added that, “So far Kenya has not seen an increase in poaching.”

Steady commitment

FLIR takes corporate social responsibility seriously and sees its role in the Kifaru Rising project as a steady commitment. Jepson said that in working with the rangers he heard the same story over and over again about how NGOs had come in in the past, gave them equipment, and then left—leaving the park rangers to fend for themselves. Batteries would die and they could not get replacements anywhere in Kenya, so they would just have to just stop using the equipment. FLIR is committed to providing equipment that requires as little maintenance as possible with the highest reliability, and the company has committed to being there if they need support. According to Loucks, “the WWF is hoping that in 10 years they can demonstrate that thermal technology is possible to adopt in other parks and by other governments, and that we will be part of the solution to support their work in conserving their wild spaces and wildlife.” World Wildlife Fund’s goal is to get to zero poaching of rhinos and other highly endangered or poached species. Loucks concluded that, “We think combining cutting edge technology like thermal cameras from FLIR with traditional conservation knowledge and experience of wildlife rangers is an important and successful way to help achieve this goal.”

Written by Anne Fischer, Editorial Director, Novus Light Technologies Today

Back to Features

Back to Features