Light waves can be defined by three fundamental characteristics: their colour (or wavelength), polarisation and direction. While it has long been possible to selectively filter light according to its colour or polarisation, selectivity based on the direction of propagation has remained elusive.

But now, researchers from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) have produced a system that allows light of any colour to pass through only if it is coming from one specific angle; the technique reflects all light coming from other directions. This new approach could ultimately lead to advances in solar photovoltaics (PV), detectors for telescopes and microscopes and privacy filters for display screens. The work is described in a paper appearing this week in the journal Science, written by MIT graduate student Yichen Shen, professor of physics Marin Soljačić and four others.

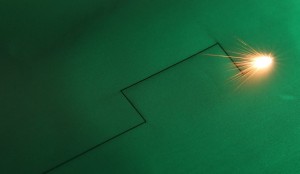

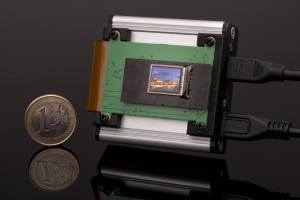

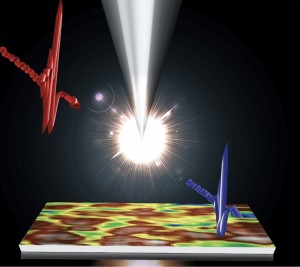

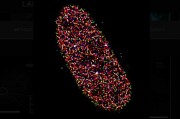

The new structure consists of a stack of ultrathin layers of two alternating materials where the thickness of each layer is precisely controlled. According to Soljačić, at the interface between two materials, you will generally have some reflections. But at these interfaces between materials, there is an angle called the “Brewster angle.” When you come in at that exact angle and the appropriate polarisation, there will be no reflection at all.

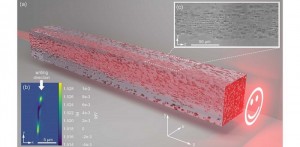

While the amount of light reflected at each of these interfaces is small, by combining many layers with the same properties, most of the light can be reflected away, except for the light that’s coming in at precisely the right angle and polarisation. Using a stack of about 80 alternating layers of precise thickness, Shen says that they can reflect light at most of the angles over a broad band of colours, which is the entire visible range of frequencies.

Previous work had demonstrated ways of selectively reflecting light except for one precise angle but those approaches were limited to a narrow range of colours of light. The new system’s breadth could open up many potential applications, the team says.

According to Shen, this discovery could have major applications in energy, especially in solar thermophotovoltaics (i.e., harnessing solar energy by using it to heat a material, which in turn radiates light of a particular colour). That light emission can then be harnessed using a PV cell tuned to make maximum use of that colour of light. But for this approach to work, it is essential to limit the heat and light lost to reflections and re-emission. The ability to selectively control those reflections could improve efficiency.

The findings could also prove useful in optical systems, such as microscopes and telescopes, for viewing faint objects that are close to brighter objects: for example, a faint planet next to a bright star. By using a system that receives light only from a certain angle, such devices could be better able to detect faint targets. The filtering could also be applied to display screens on phones or computers, so only those viewing from directly in front could see them.

In principle, the angular selectivity can be made narrower simply by adding more layers to the stack, the researchers say. For the experiments performed so far, the angle of selectivity was about 10°; roughly 90% of the light coming in within that angle was allowed to pass through. While these experiments were done using layers of glass and tantalum-oxide, Shen says that in principle any two materials with different refractive indices could be used.

The team also included MIT research scientist Ivan Celanovic; associate professor of mathematics Steven Johnson; John Joannopoulos, the Francis Wright Davis Professor of Physics; and Dexin Ye of Zhejiang University in China. The work was supported in part by the US Army Research Office, through MIT’s Institute for Soldier Nanotechnologies, and the US Department of Energy, through the MIT S3TEC Energy Research Frontier Center.

Back to News

Back to News