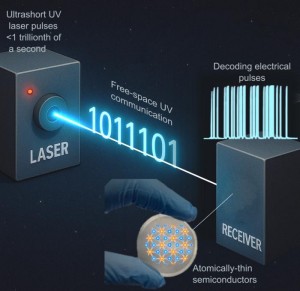

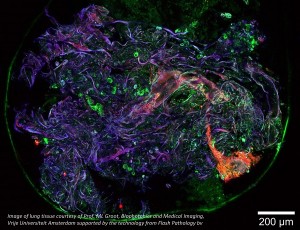

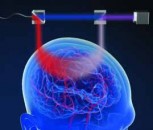

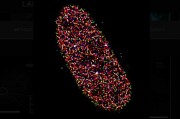

Detecting trace quantities of explosives, chemical or biological agents on a variety of surfaces is challenging—especially from a distance without physically collecting a sample. Spectroscopic techniques have been used, but even though they can be highly selective, they have poor sensitivity. Researchers are increasingly using thermal infrared imaging techniques because they can be safely used from a distance.

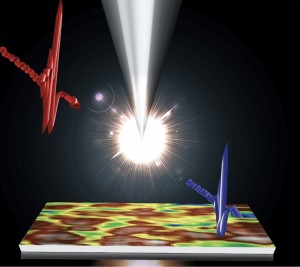

The concept behind thermal infrared imaging is, when a compound absorbs infrared light, it heats and re-emits most of the absorbed energy at different infrared wavelengths. These emitted wavelengths can be seen by the infrared camera and then analyzed so that the type of explosive can be determined. Researchers at the United States Naval Research Laboratory in Washington, DC, have combined the best of both worlds by pairing thermal imaging with spectroscopy in a Photo-Thermal Infrared Imaging Spectroscopy (PT-IRIS) technology. This photo-thermal infrared approach meets the goals of stand-off detection, which include being eye and skin safe, providing real-time analysis and being adaptable to other types of threats.

Vaporizing explosives with sniffers

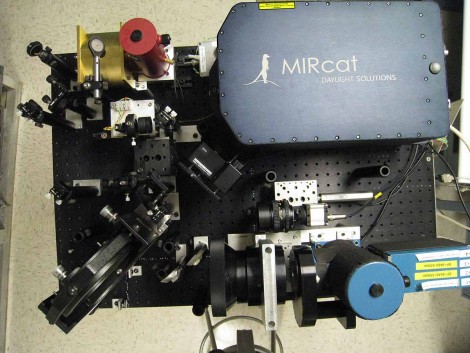

PT-IRIS has been developed over about the last ten years. The original motivation, according to Chris Kendziora, Research Scientist at the Naval Research Lab, was to try to vaporize explosives as a means to detect them using explosives “sniffers”. Emphasizing an all-optical approach, they developed the PT-IRIS system, and they worked with several different laser sources including CO2 and Fabry Perot quantum cascade lasers (QCL) before settling on the external cavity QCL, primarily for its tunability.

Discriminating one compound from another

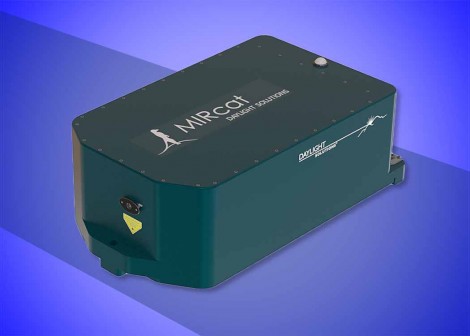

The PT-IRIS system they are working with today features a multi-QCL system (the MIRcat laser from Daylight Solutions), which can be tuned over ~800 cm-1 (~5200 nm).

According to Kendziora, the PT-IRIS system is able detect TNT and RDX as well as improvised explosives that might contain ammonium nitrate and precursor materials. One challenge is being able to discriminate one compound from another. “As soon as you mix things together it becomes more challenging for any spectroscopy.”

Building a matrix

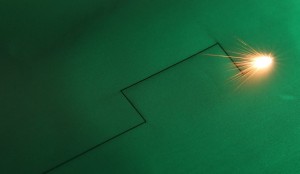

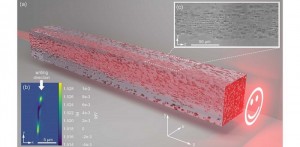

In the PT-IRIS approach, the QCLs are tuned to strong absorption bands in the analytes and directed to illuminate an area on a surface of interest. “Using tunable spectroscopy, you can constantly change the wavelength, which means you also change the power, shape and position,” Kendziora noted. These changes require extensive system calibrations. For testing, the researchers generate sample coupons with combinations of analytes on a substrate. They pick a substrate such as white paint, glass or plastic, put a chemical on top of it, and then measure—and they do that through several permutations of a substrate against the different analytes they’re looking for. All the while, they are building a matrix of four or five different threat or benign chemicals against four or five different substrates. “Sometimes we do this on a pixel by pixel basis to see whether we can detect it or not,” Kendziora added.

With the basic principle and theory of the detection system behind them, researchers at the Naval Research Lab are working through the Technology Readiness Levels to bring PT-IRIS to commercialization. Currently at about a level five (with 9 being ready for commercialization), the researchers are working toward demonstrating a prototype system in a relevant environment. “We are hoping to transition this technology to a commercial partner who will eventually enable it for use to protect our warfighters as well as for Homeland Security applications,” Kendziora concluded.

Written by Anne Fischer, Managing Editor, Novus Light Technologies Today

Back to Enlightening Applications

Back to Enlightening Applications