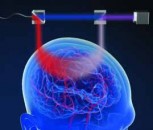

Researchers at the University of Arkansas have developed a wireless health-monitoring system that is a wearable nano-sensor that helps detect the severity of a head injury by quantifying the force of impact.

The system includes a dry, textile-based nanosensor and accompanying network that detects early signs of traumatic brain injury by continuously monitoring various brain and neural functions.

Vijay Varadan, Distinguished Professor of electrical engineering said, “In real time, our system continuously monitors neural activity and recognizes the signs and symptoms of traumatic brain injury, such as drowsiness, dizziness, fatigue, sensitivity to light and anxiety.”

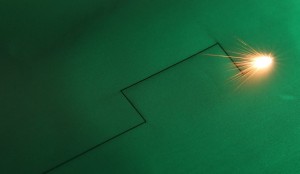

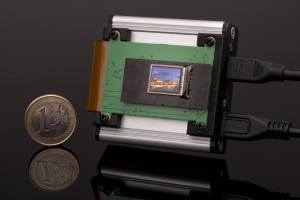

The system is a network of flexible sensors woven or printed into a skullcap worn under a helmet. The sensors are built with carbon nanotubes and two- and three-dimensional, textile nanostructures grown at the University of Arkansas. The system uses Zigbee/Bluetooth wireless telemetry to transmit data from the sensors to a receiver, which then transmits the data via a wireless network to a remote server or monitor, such as a computer or a smartphone. A more powerful wide-area wireless network would allow the system to detect large quantities of data taken continuously from each player on the field and transmit the data to multiple locations — a press box, ambulance and hospital, for example.

The sensors have considerable power and capability to monitor sensitive neural and physiological activity, Varadan said. Under stress due to impact, the sensor chips are sturdier than printed circuit-board chips and can withstand high temperatures and moisture.

The system includes a pressure-sensitive textile sensor embedded underneath the helmet’s outer shell. This sensor measures intensity, direction and location of impact force. The other sensors work as an integrated network within the skullcap. These include a printable and flexible gyroscope that measures rotational motion of the head and body balance and a printable and flexible 3D accelerometer that measures lateral head motion and body balance.

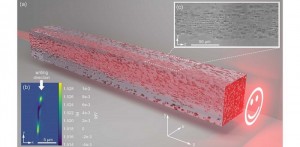

The cap also includes a collection of textile-based, dry sensors that measure electrical activity in the brain, including signs that indicate the onset of mild traumatic brain injury. These sensors detect loss of consciousness, drowsiness, dizziness, fatigue, anxiety and sensitivity to light. Finally, the skullcap includes a sensor to detect pulse rate and blood oxygen level.

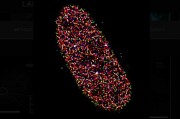

A modified sensor can evaluate damage to nerve tissue due to force impact. This sensor records electrical signals that construct a spatiotemporal image of active regions of the brain. Varadan said these low-resolution images can substitute for conventional neuro-imaging technology, such as MRI and computerized tomography (CT scan).

Varadan and researchers in his laboratory have tested the system on a small scale for real-time application. The researchers plan to test the system during an actual game this fall.

Varadan and medical researchers previously developed a related, wireless health-monitoring system that snaps onto a sports bra or T-shirt. This system gathers critical patient information and communicates that information in real time to a physician, hospital or the patient. This technology is being developed commercially.

Back to News

Back to News