The 2014 Nobel Prize in Medicine will be awarded to John O'Keefe and jointly to wife and husband team, May‐Britt Moser and Edvard I. Moser for their discoveries of cells that constitute a positioning system in the brain.

The positioning system, is being called "inner GPS" in the brain that makes it possible to orient ourselves in space, demonstrating a cellular basis for higher cognitive function.

In 1971, John O´Keefe, now Director at the Centre in Neural Circuits and Behaviour at University College London, discovered the first component of this positioning system. He found that a type of nerve cell in an area of the brain called the hippocampus that was always activated when a rat was at a certain place in a room. Other nerve cells were activated when the rat was at other places. O'Keefe concluded that these "place cells" formed a map of the room.

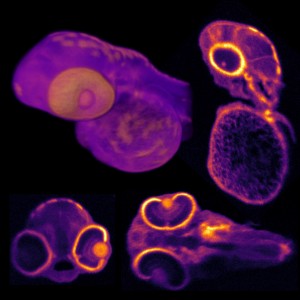

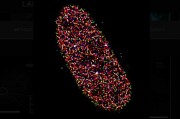

More than three decades later, in 2005, May‐Britt and Edvard Moser, who are now based in scientific institutes in the Norwegian town of Trondheim, discovered another key component of the brain’s positioning system. They identified another type of nerve cell, which they called "grid cells", that generate a coordinate system and allow for precise positioning and pathfinding. Their subsequent research showed how place and grid cells make it possible to determine position and to navigate.

John O´Keefe and the place in space

John O´Keefe discovered that certain nerve cells were activated when the animal assumed a particular place in the environment. He could demonstrate that these "place cells" were not merely registering visual input, but were building up an inner map of the environment. O’Keefe concluded that the hippocampus generates numerous maps, represented by the collective activity of place cells that are activated in different environments. Therefore, the memory of an environment can be stored as a specific combination of place cell activities in the hippocampus.

May‐Britt and Edvard Moser find the coordinates

May‐Britt and Edvard Moser were mapping the connections to the hippocampus in rats moving in a room when they discovered an astonishing pattern of activity in a nearby part of the brain called the entorhinal cortex. Here, certain cells were activated when the rat passed multiple locations arranged in a hexagonal grid. Each of these cells was activated in a unique spatial pattern and collectively these "grid cells" constitute a coordinate system that allows for spatial navigation. Together with other cells of the entorhinal cortex that recognize the direction of the head and the border of the room, they form circuits with the place cells in the hippocampus. This circuitry constitutes a comprehensive positioning system, an inner GPS, in the brain.

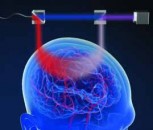

Brain imaging finds place for maps in the human brain

Recent investigations with brain imaging techniques, as well as studies of patients undergoing neurosurgery, have provided evidence that place and grid cells exist also in humans. In patients with Alzheimer´s disease, the hippocampus and entorhinal cortex are frequently affected at an early stage, and these individuals often lose their way and cannot recognize the environment. Knowledge about the brain´s positioning system may, therefore, help us understand the mechanism underpinning the devastating spatial memory loss that affects people with this disease. The discovery of the brain’s positioning system represents a paradigm shift in our understanding of how ensembles of specialized cells work together to execute higher cognitive functions. It has opened new avenues for understanding other cognitive processes, such as memory, thinking and planning.

Back to News

Back to News