Some people might consider mucus an icky bodily secretion best left wrapped in a tissue but, to a group of researchers from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, mucus is an endlessly fascinating subject. The team has developed a way to use gold nanoparticles and light to measure the stickiness of the slimy substance that lines our airways. The new method could help doctors to better monitor and treat lung diseases such as cystic fibrosis and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD).

The research team will present their work at The Optical Society’s (OSA) 98th Annual Meeting, Frontiers in Optics (FiO) 2014, being held on 19-23 October at the JW Marriott Tucson Starr Pass Resort in Tucson, Arizona (US).

According to Amy Oldenburg, a physicist at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill whose research focuses on biomedical imaging systems, people who suffer from certain lung diseases have thickened mucus. Healthy adults have hair-like cell appendages called cilia that line the airways and pull mucus out of the lungs and into the throat. But if the mucus is too thick it can become trapped in the lungs, making breathing more difficult and failing to remove the pathogens that can cause chronic infections.

Doctors can prescribe mucus-thinning drugs but have no good way to monitor how the drugs affect the thickness of the mucus in various places inside the body. This is where Oldenburg and her colleagues’ work may help.

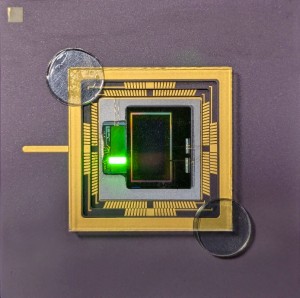

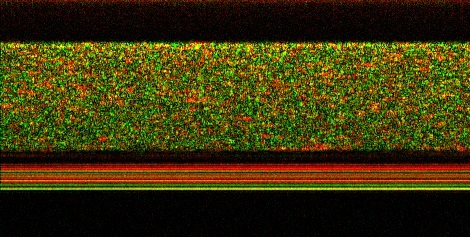

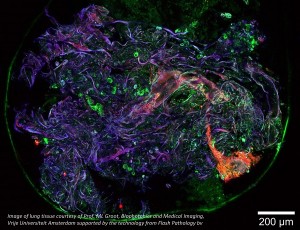

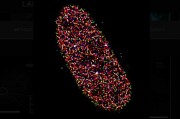

This image, captured by the UNC team, shows gold nanorods diffusing into a layer of mucus. The speckles in the top part of the image are due to rapid light intensity fluctuations caused by the gold nanorods as they move through the mucus. The black layer underneath is human lung cells and the lack of green speckle shows that the nanorods have not penetrated the cells. The lines of solid color are the membrane. Credit: Amy Oldenburg, et al/UNC

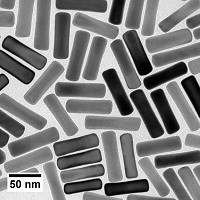

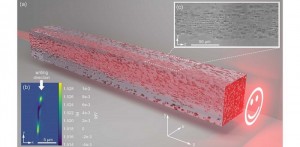

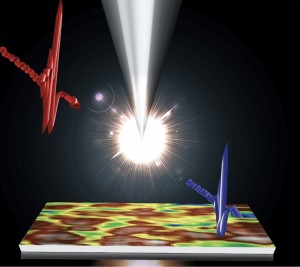

The researchers placed coated gold nanorods on the surface of mucus samples and then tracked the rods’ diffusion into the mucus by illuminating the samples with laser light and analysing the way the light bounced off the nanoparticles. The slower the nanorods diffused, the thicker the mucus was. The team found this imaging method worked even when the mucus was sliding over a layer of cells, an important finding since mucus inside the human body is usually in motion.

According to Oldenburg, monitoring how well mucus-thinning treatments are working in real-time may enable us to choose better treatments and tailor them to the individual.

It will likely take five to 10 more years before the team’s mucus-measuring method is tested on human patients, Oldenburg said. Gold is non-toxic but for safety reasons the researchers would want to ensure that the gold nanorods would eventually be cleared from a patient’s system.

According to Nozomi Nishimura, of Cornell University and one of the FiO subcommittee chairs, this is an example of interdisciplinary work in which optical scientists can meet a specific need in the clinic. As these types of optical technologies continue to make their way into medical practice, both patient care and the market for the technology will improve.

The team is also working on several lines of ongoing study that will someday help to bring their monitoring device to the clinic. They are developing delivery methods for the gold nanorods, studying how their imaging system might be adapted to enter a patient’s airways and further investigating how mucus flow properties differ throughout the body.

Presentation FTu5F.2, “Imaging Gold Nanorod Diffusion in Mucus Using Polarization Sensitive OCT,” takes place Tuesday, 21 October at 4:15 p.m. Mountain Standard Time (MST) in the Tucson Ballroom, Salon A at the JW Marriott Tucson Starr Pass Resort.

Back to News

Back to News