In many production environments, vision-based systems are deployed to inspect products for quality assurance purposes. One means to do so is to capture images of such products and compare them with a known good part referred to as a ‘golden template’. By subtracting the image of the part under test from the golden template, any defects can then be highlighted by the vision system.

In reality, however, many products are not manufactured with the necessary fidelity to be tested against a golden template. So while the technique can be effective for certain inspection tasks, it does not work well where parts have some natural degree of variation. Although vision system developers can create variants in such templates to overcome the problem, this can be a time-consuming process.

To resolve that issue, Dr. Jason Dale, the founder of Vision Experts (UK), recently developed a new software tool called FlexInspect, which is now offered as part of Stemmer Imaging’s (Germany) Common Vision Blox (CVB) software library.

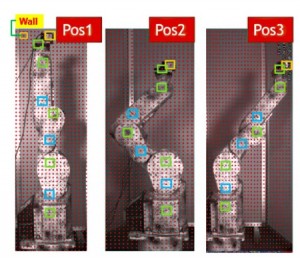

Rather than compare an image of a product under test to a golden template, the FlexInspect software takes a model-based learning and verification approach. In the learning phase, the software analyses images of a number of ostensibly similar products from which it builds a model that represents the natural variation in their appearance.

The software is able to create an image that highlights the key differences between the product under test and the model itself.

When presented with a new image of a product at the verification stage, the software determines the degree by which the appearance of the product varies from the model created during the learning phase. It is then able to create an image that highlights the key differences between the product under test and the model itself. The variant can either be adding to the model, or the product rejected.

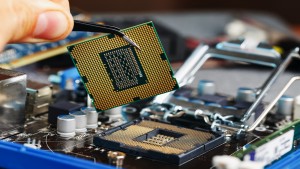

“To accelerate the execution time of the FlexInspect image processing software,” said Dr. Dale, “it was developed at the outset to take advantage of Intel multi-core CPUs with two or more independent central processing units."

To do so, the software does not perform mathematical operations on entire images, but on sub images, or pixel blocks, within each of the images presented to it. Each of these pixel blocks can be processed independently according to the number of core CPUs in the system.

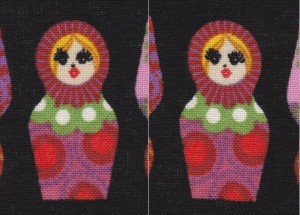

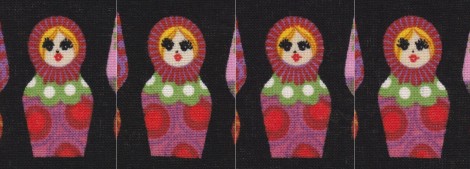

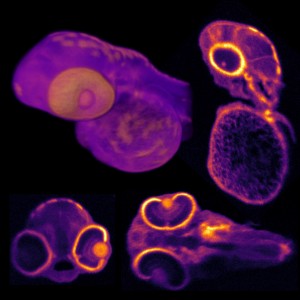

Figure 1: Four different images of a doll were used to train the software model. A close look at the four shows that a degree of warping has occurred, leading to changes in detail, especially around the eyes and mouth.

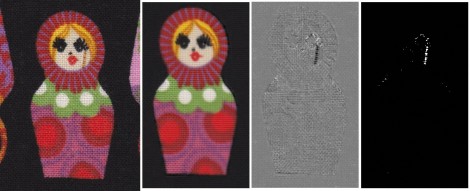

Figure 2: From left to right: An input image captured at the verification stage. A best fit image built from the model. The difference between the best fit image and the input image. Areas of major difference between the two highlighted using an optional image thresholding operation.

In the training mode, for example, the software computes the statistically most significant variations between the values of rows of pixels in several blocks within an image. The results from each block are then combined to provide a complete picture of the statistical variation across the whole image. After performing the same operation on hundreds of images of similar products, the software builds a model which contains all the known acceptable variations between the pixels in the images of that particular product.

Closely matched result

During verification in a production environment, an image of the sample to be inspected is presented to the software to produce a further image that represents the best fit between the observation and the statistical model. The difference between the image produced from this best fit calculation and the observed image of the sample itself highlights how closely the features in the new image matched the model. A further optional thresholding operation can be performed on the image to reveal any major differences.

The task of exploiting the parallel processing capabilities of Intel multi-core CPUs was made easier by the use of the complier extensions found in the Open MP standard. These complier extensions process a program and add parallelism into the code without a developer needing to significantly rewrite it. In the case of the FlexInspect software, the compiler extensions enabled the high-level tasks of processing the blocks in a single image to be spread across the available cores in the microprocessor.

The use of the optimized processing functions found in the Integrated Performance Primitives (IPP) library, on the other hand, enabled the low-level image processing instructions in the software to take advantage of the SIMD (Single Instruction Multiple Data) instructions on Intel processors. SIMD instructions are useful when exactly the same operation is performed on multiple data objects. In the case of the FlexInspect image processing algorithm, one instruction could be called to perform the same operation on several rows of pixels within each block to determine the statistically significant variations between them.

To take advantage of the IPP primitives, Dr. Dale deconstructed his algorithm into the discrete mathematical processing functions that were to be performed on each block of the image. He then used the equivalent software functions in the IPP library from which to reconstruct it. Not only did the move save development time, but also added further parallelization to the computational tasks.

By using the Open MP complier directives and functions from the IPP library, every block of the image could be processed in parallel and the individual arithmetic functions performed on the pixels within the blocks accelerated. Having tested the FlexInspect software out on a single core, dual core and quad core processors, Dr. Dale claims that it scales in performance almost directly in proportion to the number of core processors that are used.

“The new tool is currently being put to use in several product inspection systems where it has overcome the traditional limitations of comparing samples under test to golden templates, providing manufacturers with a more appropriate means to inspect products with some natural variation,” Dr. Dale concluded.

Written by Dave Wilson, Contributing Editor, Novus Light Technologies Today

Back to Features

Back to Features